Intro to Process Automation (Part 2) - Making Models Executable

Variables, Workers And Deployments in Camunda

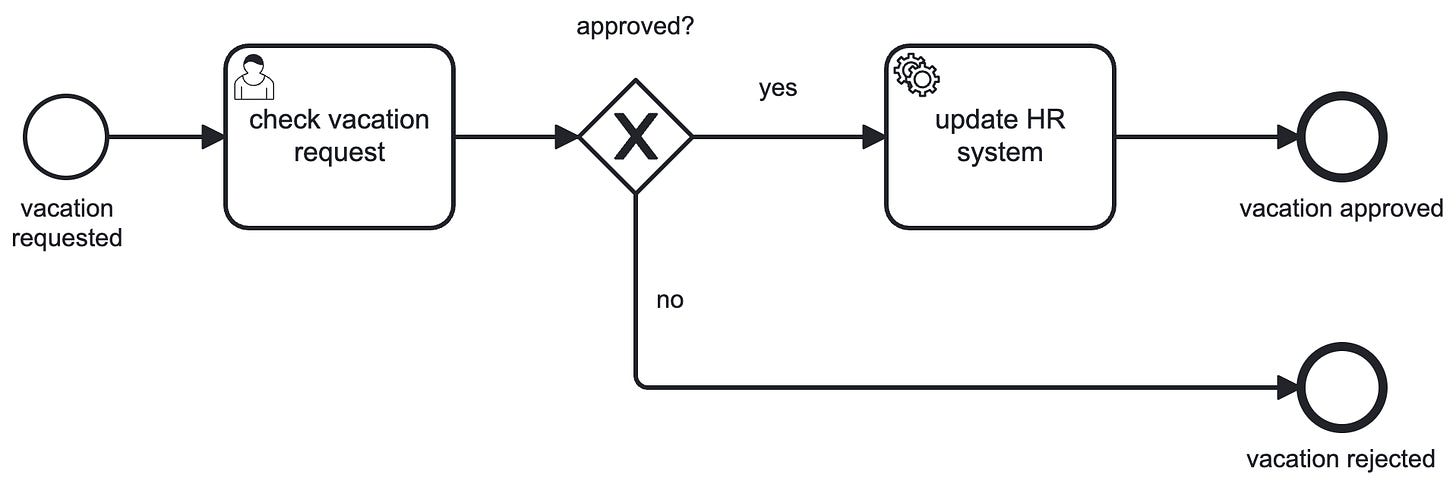

In the first part of this series, I showed why automation matters and why BPMN diagrams alone are not enough. The next logical step is to take a model like the vacation request process and prepare it for execution. While the diagram already describes the flow of activities, the engine requires more detail to understand how to run it.

This article explains what makes a process model executable, how variables and tasks are prepared for execution, and what happens when the process is deployed to Camunda. The vacation request process will again serve as the running example.

What Makes a Model Executable

A BPMN diagram that exists only for documentation does not need to care about data, system calls, or user interactions. For execution, these elements become essential. The model must specify which data is carried through the process, which steps are automated, and which require human input. Without this information, the engine cannot coordinate work.

In the vacation request example, the executable model needs to define the variables that represent the request itself: the employee’s identifier, the start date, the duration of the vacation, and the approval decision. Tasks such as “check vacation request” must be mapped to either a user task, where Camunda waits for manual input, or a service task, where an external system or worker completes the task automatically. This transformation from descriptive to executable turns the diagram into a precise technical specification.

Preparing for Execution

Execution in Camunda depends on process variables. Variables are the data elements that are moved through the process instance and act as input for task execution. They can be set, read or modified during the process execution.

Defining them carefully is crucial because they drive both the flow and the data exchange. For example, an exclusive gateway in BPMN routes the process based on the value of a variable. If the variable is missing or not set correctly, the process will fail at that point. The same applies to deadlines: a timer boundary event can read a variable that specifies how long a manager has to respond before the request is escalated. In this way, variables are not only containers of information but also control the logic of the process.

The following elements are used to capture and use variables in the process.

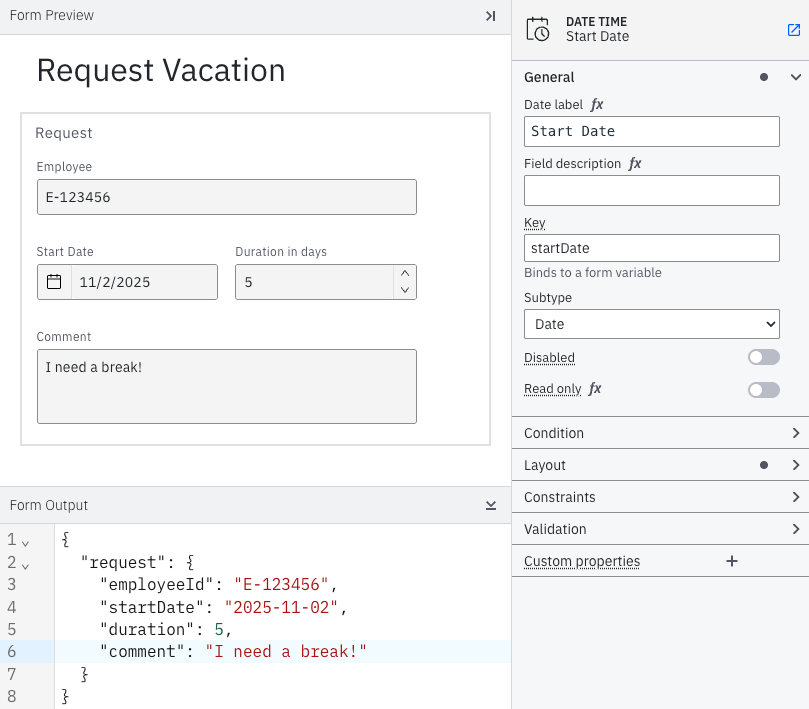

User Forms

User Forms are used to capture process variables through human interaction in a User Task. They can be used to start a process or to involve humans later in the process.

In the vacation request example, the process starts e.g. by capturing the employee’s ID, the start date and the duration of the vacation, and possibly the reason for the request. These values are stored as process variables, which means the engine can access them at any point in the process.

To achieve this, a form can be linked to a None Start Event by its key, and the Camunda engine will automatically show it in the assigned User Task in the task list.

User Tasks

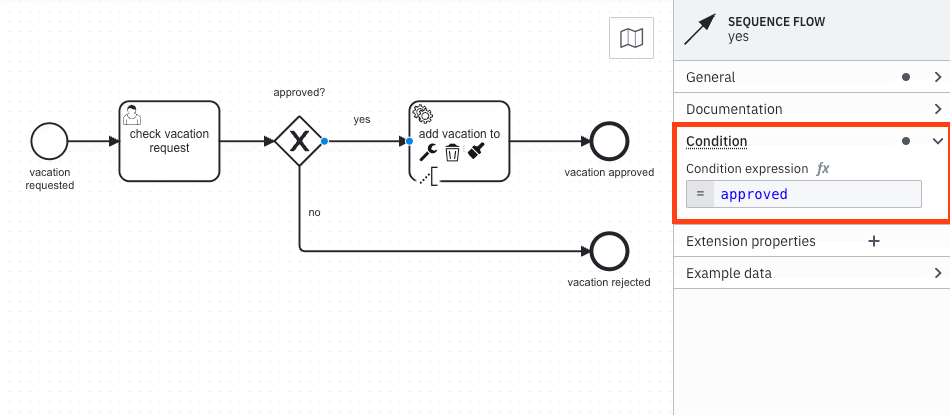

User tasks are handled differently but follow the same principle of variable mapping. When the engine reaches a user task, it creates a pending task and makes selected variables available in a user form as well. In the vacation request process, the manager approval task needs to show the employee’s name, the requested dates, and any comments provided by the employee. These variables are explicitly mapped into the user task so the manager has the necessary context. When the manager completes the task, the approval decision is written back into the process as a variable, allowing the process to continue.

For this, the condition of each outgoing flow of an XOR gateway must be evaluated. The first flow resulting in a logical true will be taken. The expression approved is identical to approved=true and can be abbreviated.

Service Tasks

Service Tasks in Camunda require an external worker to perform the actual work. Workers are small Java programs that subscribe to specific task types.

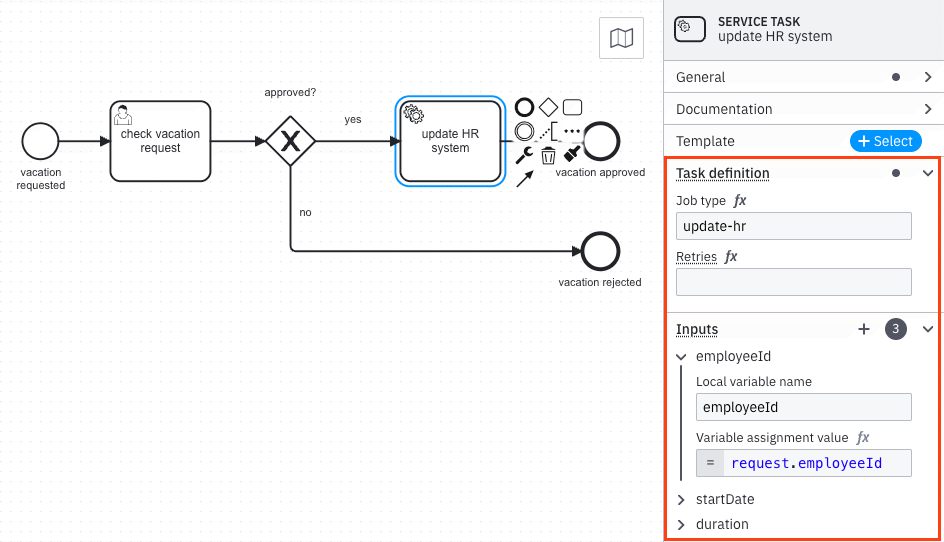

In the vacation request process, an automated “Update HR System” step might be implemented by a worker that listens for tasks of type update-hr.

When the engine reaches this service task, it creates a job with the relevant variables. Those variables must be mapped into the task so the worker has all the information it needs, for example, employeeId, startDate and duration. The worker fetches the job, performs the update in the HR system, and signals completion back to the engine, possibly adding new variables such as updateStatus.

At this stage, the process model has all the necessary details for execution. Every task has a clear path to completion, either by a person or by a worker. Every decision point is based on well-defined variables, and variable mappings ensure that the right information is delivered where it is needed. The model is still the same BPMN diagram as before, but enriched with the technical details that make it executable.

Deployment in Camunda

Once the model is executable, it must be deployed to the engine. Deployment takes the BPMN XML file and registers it as a process definition. Camunda stores the definition, assigns it a version number, and makes it available for instantiation. Each deployment creates a new version, while existing process instances continue running on the version they were started with.

In practice, deployment can be done directly from the Camunda Modeler, via the REST API, or integrated into a automation pipeline. In the vacation request example, deployment means that the process definition is now available in the engine. From this point on, employees can start vacation requests as actual process instances, and the engine will manage their execution according to the model.

From Diagram to Running Process

The lifecycle of a process in Camunda moves from modeling to execution in clear stages. First, the BPMN diagram is made executable by defining variables, tasks, and assignments. Then the diagram is deployed, which registers it as a definition inside the engine. Finally, users or systems can start new process instances based on that definition.

In the vacation request scenario, one process definition controls all vacation requests. Each request submitted becomes an instance of that definition. The engine ensures that every instance follows the same flow, applies the same rules, and records the same data points. This consistency is the key difference between a diagram on paper and a process running in Camunda.